INTERVIEW: Experience of Bias Detailed by RHS ’20 Alum

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter march in Rye, the LGBTQ+ event on the village green and other activity detailing experiences of bias in our community and in our schools, MyRye.com will be running interviews with those who have been impacted by bias in Rye and others who are working on ways to address these inequities.

Our second interview is with Mika Mizobuchi, a 2020 Rye High School graduate. If you missed it, be sure to see our first interview with Brigitte Fleitas, a 2018 graduate.

Your name: Mika Mizobuchi

MyRye.com: What is your ethnicity and how else do you identify?

Mizobuchi: I am proudly Japanese, and I was born in California. I’ve lived in Tokyo for about five and a half years and I’ve lived in other places as well.

Does Rye have a problem with bias? And in your experience, is it isolated to certain people, traditions, or institutions, or more pervasive?

Mizobuchi: The term ‘bias’ barely touches upon on the problems this community has with racism. Racism is certainly not something that exists isolated—it stems from ignorance and prejudice that are so deeply rooted, it is seen as a norm or even a tradition.

You moved to Rye your freshman year of high school after having lived in Tokyo, New York City, South Africa, and Los Angeles. How aware were you of your ethnicity and any related bias in Rye compared to these other places?

Mizobuchi: To be honest, I don’t remember much of LA or Pretoria (South Africa). However, what I do know is that I was not exposed to the abstract topic of race and ethnicity yet—it was not until elementary school in NYC that I realized that the simple fact of my ethnicity can determine how I am treated by others. What I find pretty funny is that it was in the city most known for its racial diversity, that I had this eye-opening experience about my relationship with racism. Rye is no different than Manhattan, but people here barely interact with BIPOC, which leads to lack of knowledge and effort to dismantle the system they benefit from, whether they are aware of it or not.

You graduated from Rye High School in 2020. How did your experience with bias change or evolve as you went through your four years of high school?

Mizobuchi: I suddenly went from going to a middle school with mostly Asian students to a high school with almost all white students. For this, I have experienced racism all throughout high school. However, as the years went by, I realized that in some ways I have to thank Rye. I say this because my experiences here were the catalyst that pushed me to explore my identity as an Asian American, and the complexities of my relationship with racism. Time and education helped me look at racism through a different lens and advocate for causes I believe in.

You said, “Rye is a bubble”. Explain to people what you mean by this. What is the manifestation of this in your experience?

Mizobuchi: When a white and wealthy person grows up in a community like Rye, they are not exposed to experiences that other people face when they don’t fit these descriptions. ‘The bubble’ is made out of white comfort and privilege that shields white people from the realities of racism and the consequences of perpetuating it. A white and wealthy kid can graduate high school without ever learning about anti-racism. Proven in the stories posted on the BIPOC Instagram account, white people can openly be racist and face no consequences. If anyone speaks out, they are often ignored, ostracized, or gaslighted.

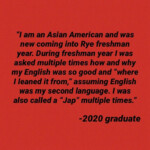

When you arrived in Rye from Tokyo many in Rye High School were surprised you spoke English. How were the comments made, and how did they make you feel?

Mizobuchi: Many were mind-blown that I spoke fluent English. They would exclaim “your English is so good!”, followed by the question “how are you so good at it?” I would then have to explain how I was born here and received the same American education just like everyone else. At first, I didn’t understand how ridiculous the question was, but I realized that for white people to ask this question was, unintended or not, microaggression, because they assumed that I was ‘not from here’. It made me feel like a foreigner in a country that I was born in. When did the new white kid ever get asked that question?

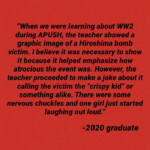

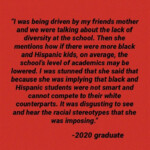

(PHOTO: These experiences from Mika Mizobuchi were posted on the BIPOC at Rye High School Instagram account.)

In your AP US history class, your teacher made an off-color joke when teaching about the World War II atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Explain what happened and how it made you feel.

Mizobuchi: The ridiculously ignorant joke that this teacher made felt very personal not only because I am Japanese, but my father’s family is from Hiroshima. When the teacher said it, I heard some nervous chuckles and one girl even started laughing out loud. It was shocking and it took a while to process what happened. When you’re constantly hearing racist jokes and comments, you tend to become numb to microaggression and it even becomes difficult to instantly determine what was said was problematic or not.

Being part of the Rye High School GSA (Gay Straight Alliance) and having a summer internship with the pRYEde community group, you said the LGBTQ+ community at the high school tends to be overlooked. What is an example of this? And are there one or two obvious things that can be done to be more inclusive?

Mizobuchi: Last year, the school tried to get rid of the GSA. It was very upsetting, but not surprising, that the administration tried to shut down the only safe space for LGBTQ+ students at school. It’s both historically and culturally important to include the topic of sexuality at a discussion of race, as it is impossible to not talk about one without the other—both conversations have to be inter-sectional. One simple thing that we can all do is to understand that it is not enough to strive towards inclusivity—we all have to work towards unlearning prejudice beliefs and becoming anti-racist.

In the last several weeks, we have seen a Black Lives Matter march in Rye, as well as the aforementioned community action supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Do these events give you hope that we are moving in the right direction? Is this a milestone moment or not?

Mizobuchi: Yes, it does give me hope. Unfortunately, so many lives of BIPOC had to be lost and names be trended on Twitter for some people to finally wake up. However, I believe that we are living through the modern-day civil rights movement, and it’s very inspiring to see that many are choosing to be the right side of history. There are still very long ways to go, though.

The Rye City School District and its board of education are forming a race task force to look at the issue of bias. What voices need to be part of this task force? And, like the last question, does this step make you hopeful?

Mizobuchi: I want to acknowledge RCSD for taking action in response to the recent events. It is disappointing, though, that BIPOC students have finally given the chance to be heard only after intense community pressure and a global-wide civil rights movement.

Every single voice needs to be part of this task force: BIPOC, white, LGBTQ+, disabled, abled, low income, high income, students, alumni, parents, and faculty. To remind everyone, there are not going to be immediate results just by changing the summer reading list. Becoming anti-racist takes time and a serious amount of work. However, I am looking forward to the change in curriculum and being part of something that will be the first step in the right direction.

Thank you, Mika!