RyeGPT People of Note: Civil Rights Activist, Journalist & Author Dorothy Sterling

RyeGPT People of Note is a series highlighting individuals who have a connection to the City of Rye. In the series we ask OpenAI’s ChatGPT to prepare a biography and explain the individual’s connection to Rye.

We welcome your feedback on this series – the use of artificial intelligence, the accuracy and usefulness of each article and your assistance in understanding other pertinent insights related to the person’s connection to Rye.

You can add comments at the bottom of each article or you can send feedback via Tips & Letters.

Early Life and Education

Dorothy Sterling (née Dannenberg) was born on November 23, 1913, in New York City. She was the daughter of a lawyer and a schoolteacher, growing up in a comfortable middle-class environment. She attended Wellesley College and later transferred to Barnard College, where she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1934. While she initially aspired to become a botanist, a professor dissuaded her from this path, citing limited opportunities for women in the field. She subsequently pursued studies in philosophy but ultimately found her calling in journalism and literature.

Career in Journalism and Transition to Literature

After college, Sterling began working as a journalist. She contributed to Art News and later joined the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal-era program that provided jobs to unemployed writers. This experience broadened her worldview, exposing her to diverse communities, including African American writers, Yiddish playwrights, and Greenwich Village poets.

In 1941, she secured a position at Life Magazine, first as a secretary and later as a researcher. Her talent for in-depth research led her to become assistant chief of Life’s news bureau. However, faced with the era’s gender biases—where “all writers were men, and all researchers were women”—she eventually left journalism to pursue a career as a full-time writer.

Advancing African American Representation in Literature

Sterling’s literary career was deeply rooted in social justice, particularly African American history and the civil rights movement. She authored over 35 books, including some of the earliest full-length biographies of African American figures written for children. Her landmark work, Freedom Train: The Story of Harriet Tubman (1954), brought national attention to Tubman’s life and remains in print today.

Sterling was committed to uncovering and documenting the lives of lesser-known but significant African American historical figures. Her books Captain of the Planter: The Story of Robert Smalls (1958) and The Making of an Afro-American: Martin Robinson Delany (1971) helped shed light on forgotten pioneers of Black history.

Beyond children’s literature, she also wrote books for adult audiences, including We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (1984), an anthology of letters, diaries, and firsthand accounts that brought the voices of Black women to the forefront of historical study. Another influential work, Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery (1991), chronicled the life of abolitionist and suffragette Abby Kelley, highlighting the intersections of race and gender in activism.

Activism and Connection to Rye, New York

Sterling was also involved with the Communist Party USA during the 1940s. Her concern for the plight of working people in America led her to join the party in the 1930s, a period when many individuals with progressive ideals sought refuge in its ranks. Even after departing from the party, Sterling maintained that socialism remained her long-term goal.

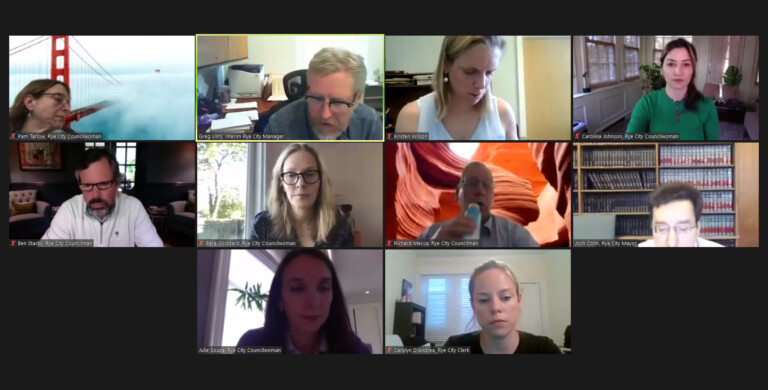

In 1948, Dorothy Sterling and her husband, fellow writer Philip Sterling, moved to Rye, New York, settling in a neighborhood on Kirby Lane North that attracted progressive intellectuals and activists. Due to their political affiliations, particularly during the McCarthy era, the Sterlings and their neighbors were viewed by some in Rye as a threat to the more conservative way of thinking. The FBI monitored their activities, including opening their mail and visiting their home. As a result, the neighborhood on Kirby Lane North was colloquially referred to as “Red Hill” by other Rye residents, reflecting its association with communist sympathizers.

The Sterlings were active members of the local NAACP chapter, working to combat racial discrimination in housing. One of their most significant contributions was exposing housing discrimination in Rye. Alongside other activists, they helped uncover racist rental practices, such as those at Rye Colony, where M. Paul Redd and his wife Orial Banks Redd were denied an apartment based on race. Sterling, along with Lotte Kunstler (wife of civil rights attorney William Kunstler), participated in a “testing” effort, in which white applicants were able to secure housing while Black applicants were turned away. Their work provided crucial evidence that helped Redd win his landmark housing discrimination case.

The Sterlings’ civil rights activism came at a personal cost. In 1961, after their son, Peter Sterling, participated in the Freedom Rides and was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, the family became targets of racist intimidation. A seven-foot-tall cross was burned on their lawn in Rye, an act meant to terrorize them into silence. Despite this, Sterling remained undeterred and continued her advocacy for racial justice.

Role in Educational Reform and Multicultural Representation

Sterling was also a vocal critic of racial bias in education. In the mid-1960s, she testified before a congressional committee led by Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (D-N.Y.) on the lack of diversity and accuracy in textbooks. She played a key role in founding the Council on Interracial Books for Children, an organization that sought to improve the portrayal of minorities in children’s literature.

Her book Mary Jane (1959), a novel about school desegregation from the perspective of a Black girl, faced boycotts in the South and parts of the North but ultimately became a bestseller and was translated into multiple languages. The book was one of the first to portray desegregation struggles through the lens of a young Black protagonist, making it a pioneering work in children’s literature.

Later Years and Legacy

Sterling continued writing well into her later years, completing her last book, Close to My Heart: An Autobiography, in 2005 at the age of 90, despite being nearly blind. She remained passionate about civil rights, history, and literature throughout her life.

She passed away on December 1, 2008, at her home in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, at the age of 95. She is survived by her two children, Peter Sterling and Anne Fausto-Sterling, as well as grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Impact and Recognition

Dorothy Sterling’s influence on literature and civil rights remains significant. She was among the first authors to insist on the representation of African Americans in children’s literature, long before multiculturalism was widely embraced. Her work not only educated generations of readers but also contributed to broader societal changes regarding race and representation in history.

Her activism in Rye, New York, particularly her role in challenging discriminatory housing practices alongside the Redds, cements her legacy as both a literary and civil rights pioneer. Through her books and activism, she helped reshape narratives about African American history and inspired future generations of scholars, activists, and writers.