Holding Court: Racism, Poverty & Smells – a History of Zoning

Holding Court is a series by retired Rye City Court Judge Joe Latwin. Latwin retired from the court in December 2022 after thirteen years of service to the City.

What topics do you want addressed by Judge Latwin? Tell us.

By Joe Latwin

At Common Law, a man (women did not necessarily have any right to own property) was free to do with his property as he wished. However, a property owner was free to contract with a buyer or neighbors to restrict the use or ownership of property. Often, Sellers or developers would include contractual provisions – restrictive covenants – that restricted the ownership and use of property. Restrictive covenants are legally enforceable obligations that are included in a property’s title deeds. They are designed to regulate and prohibit specific activities or modifications to the land by a previous owner, developer, or even a planning authority. Most restrictive covenants “run with the land” so that the covenant is not merely an agreement between the original parties, but attaches to the property itself. As a result, it binds subsequent owners regardless of whether they were the parties to the original agreement.

Many restrictive covenants prohibited the sale to or occupancy by races other than Caucasian directly. In 1911, thirty out of a total of thirty-nine owners of property fronting both sides of a street in St. Louis, signed an agreement, that was later recorded, providing in part:

. . . the said property is hereby restricted so that it shall be a condition all the time and whether recited and referred to in subsequent conveyances and shall attach to the land as a condition precedent to the sale of the same, that hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be. . . occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended to restrict the use of said property against the occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purpose by people of the Negro or Mongolian Race.

By 1945, four of the premises were occupied by Negroes, and had been so occupied for periods ranging from twenty-three to sixty-three years. In 1945, one owner contracted to sell his property to a family of Negroes. The buyers sued. The State court ordered the buyers to refrain from occupying or using the property they bought. In 1948, in Shelley v. Kraemer, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the restrictive covenant did not violate the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment since there was no State action.

However, the action of state courts and judicial officers in their official capacities enforcing the restrictive covenant was State action within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, private agreements to exclude persons of designated race or color from the use or occupancy of real estate for residential purposes do not violate the Fourteenth Amendment; but it is violative of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for state courts to enforce them. The Fair Housing Act and other laws now bar racial discrimination in housing.

There were other means of excluding “non-desirables”. Many restrictive covenants prohibited flat roofs and required structures to cost more than a certain amount – often $10,000. This meant less expensive dwellings could not be built – keeping poor people out of the neighborhood. Many of these restrictions have been overtaken by current economics. Building codes that require minimum living areas, and impose health and safety requirements (electrical, plumbing, and multiple means of egress) that push the cost of any dwelling above the amount in the restrictions. Some old restrictions had set a $2,000 cost minimum.

Some old restrictive covenants also limited the use of the property – usually to bar noxious operations – no tanneries, no breweries, no slaughterhouses – smelly uses.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s restrictions began to limit building size, create minimum setbacks and building height. Beginning in the early 1900s, municipalities started to create zoning codes. The first zoning code was in Los Angeles in 1908. New York City’s zoning code was implemented in 1916. Many suburban localities enacted zoning that often permitted only single-family housing that did not encourage or allow African-Americans to move into or use residences that were occupied by majority whites asserting their presence would decrease the value of homes.

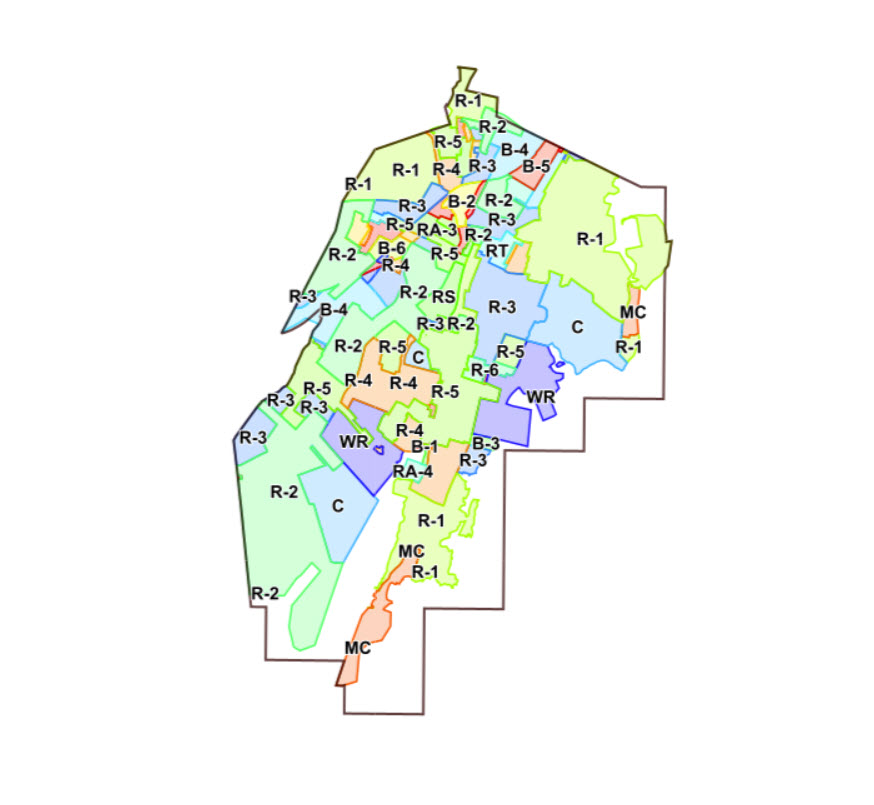

In 1922, residents of Euclid, Ohio sued to invalidate Euclid’s zoning Code claiming it diminished their property values when it zoned the property owner’s land for residential use, when the owner planned to develop industrial uses. In 1926, in Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. case, established the constitutionality of zoning laws in the United States. The Court upheld the Village of Euclid’s zoning ordinance, which restricted land use and established zoning districts, thereby affirming that such regulations are a valid exercise of police power by local governments. This opened the door to an explosion of municipal zoning codes. The Village of Rye adopted its first Master Plan. The City of Rye adopted its latest Master Plan in 1985.

Federal and State laws have also placed restrictions on the use of property to limit flooding, ensure safety, limit fire exposure, encourage diverse uses, and conserve energy. All these laws have served to undercut the need for restrictive covenants. However, restrictive covenants and zoning are mutually exclusive and co-exist. New York’s highest court said they are independent of each other in the Friends of the Shawangunks case. Do you know where the Shawangunks are?