James Fenimore Cooper and Spies in Rye

Suzanne Clary, president of the Jay Heritage Center, is a MyRye.com history correspondent. Today our history teacher tells us about spies in Rye.

Suzanne Clary, president of the Jay Heritage Center, is a MyRye.com history correspondent. Today our history teacher tells us about spies in Rye.

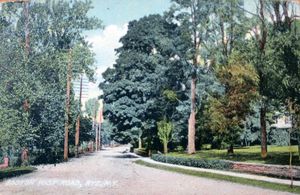

One of Rye’s most famous residents was James Fenimore Cooper, perhaps best known as author of “Last of the Mohicans.” Cooper lived in Rye just a brief time but it remained a touchstone for him throughout his life. The bucolic lands outside Manhattan provided three key elements for his first successful novel, "The Spy"– a scenic setting, believable characters, and a gripping plot with a real life twist.

(PHOTO: Portrait of author and one time Rye resident, James Fenimore Cooper.)

Cooper’s book is about a common man named Harvey Birch accused of spying for the British during the Revolutionary War in Westchester. The story opens at “The Locusts,” inspired by the Rye home of the same name that belonged to Cooper’s close friends and neighbors, the Jay family:“…the fall of the land to the level of the tide water afforded a view of the Sound* over the tops of the distant woods on its margin." Cooper further explained the Sound to readers unfamiliar with its location: " *An island more than forty leagues in length lies opposite the coasts of New York and Connecticut. The arm of the sea which separates it from the main is technically called a sound, and in that part of the country, par excellence, 'The' Sound. This sheet of water varies in breadth from five to thirty miles."

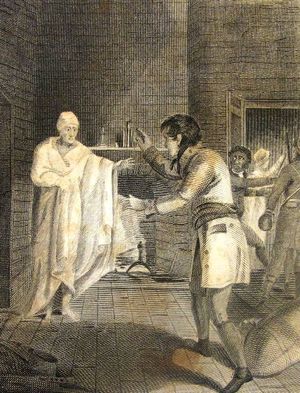

(PHOTO: Illustration from "The Spy" showing Caesar who lived, was freed and is buried in Rye on the Jay Property.)

Drawing on life, the characters in “The Spy” included Caesar, a black servant, sharing the same name as Caesar, a black slave belonging to the Jays (who was later freed and buried at the Jay farm.) "Every thing was ready, and they were about to lift Birch in their arms, for he refused to move an inch, when a figure entered the room that appalled the group; around his body was thrown the sheet of the bed from which he had just risen, and his fixed eye and haggard face gave him the appearance of a being from another world. Even Katy and Caesar thought it was the spirit of the elder Birch…”

Most importantly, the plot for this “fictional” adventure was inspired by true tales of espionage told by Revolutionary War spymaster, John Jay. Spymaster? More Americans know John Jay for being a jurist and a statesman but the CIA’s website explains very factually why John Jay is also known as the Founding Father of US counterintelligence.

As one of George Washington's closest confidantes when it came to matters of wartime security, Jay saved the future President’s life in 1776 when he uncovered a Tory scheme to enlist volunteers to sabotage New York’s defense system . The machinations included plans to capture, and possibly kill the young nation’s leader. After defusing this threat, Jay was made one of 6 members of the "Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies" created by the New York Convention on September 21, 1776.

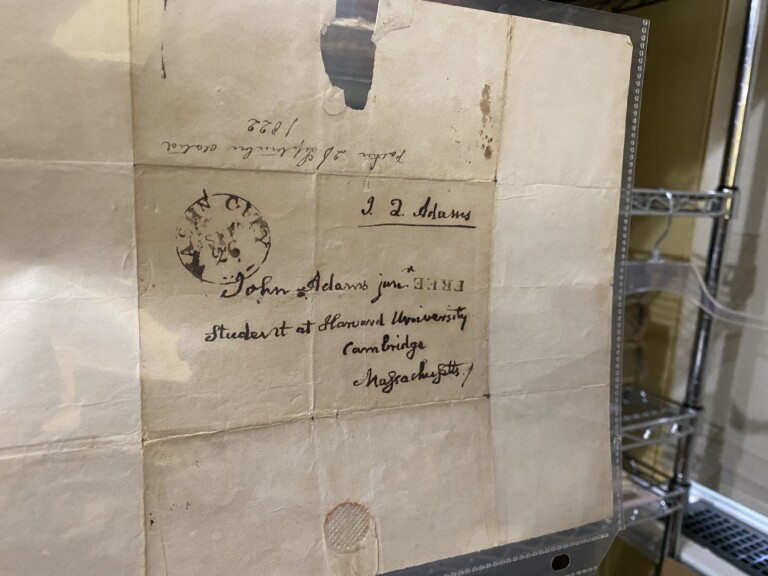

Jay even enlisted his family to help. In addition to creating secret codes of his own, John Jay recruited his brother's scientific knowhow to further safeguard important patriot transmissions. Long before there was a Q, James Jay invented "sympathetic stain," a chemical solution that acted as a reagent in revealing secret messages written in invisible ink between the lines on otherwise innocent letters. (One wonders what secrets the two Jay brothers may have created and left hidden at their boyhood home in Rye.)

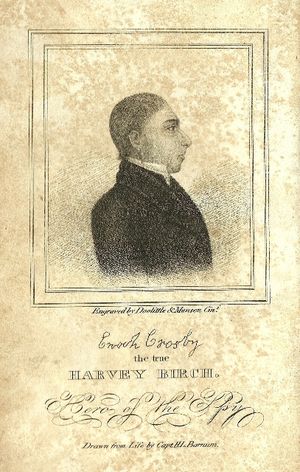

(PHOTO: 1828 Portrait of Enoch Crosby, inspiration for James Fenimore Cooper's "The Spy")

So Jay's reminiscences of his undercover role in America's fight for independence would certainly have sparked Cooper's imagination. To the public, Jay was silent on all the cooincidences in Cooper’s novel; he was especially quiet about the names of all his informants. But readers continued to press for the real identity of the central character of "The Spy." Like Jay, Cooper denied knowing the name of Jay's agent (even up to the author's death in 1851) but it was widely believed to be an unassuming shoemaker named Enoch Crosby. Unabashed speculation eventually prompted the publication of "The Spy Unmasked" in 1828 but probably the most accurate unveiling of Enoch Crosby's service was told by the old spy himself in 1832. Crosby finally confessed in writing on an application to get what was well owed him and ever more valuable and practical than literary fame — a soldier's pension.

This was a really excellent article. Thank You Mrs. Clary.