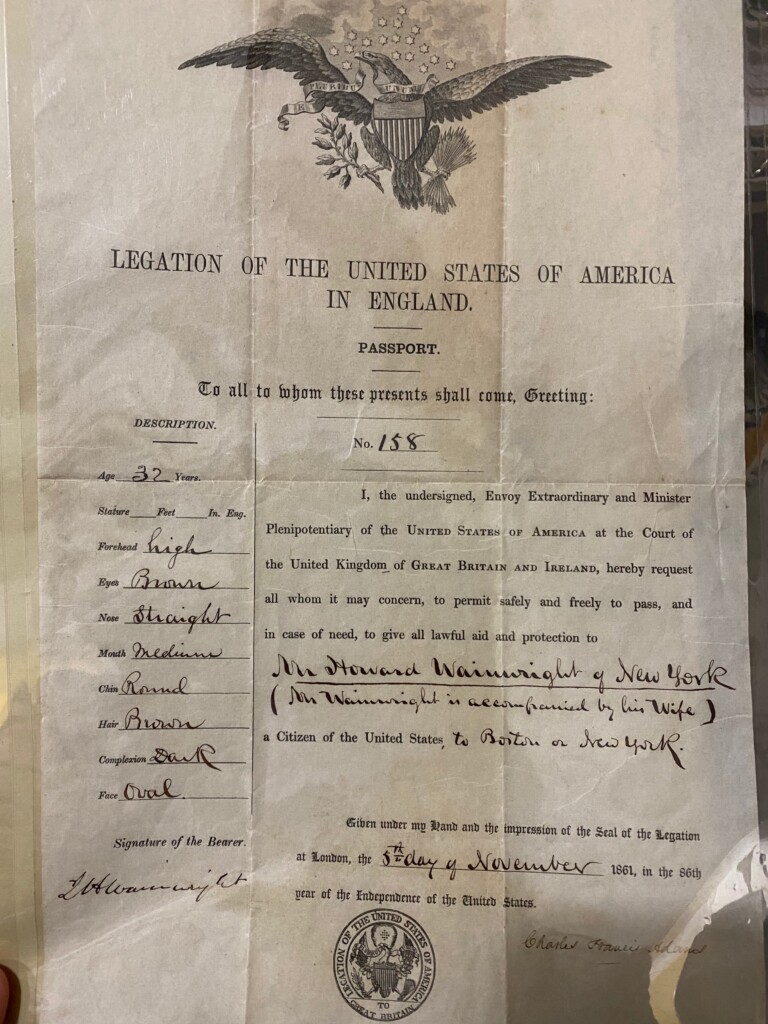

Papers from Our Past: The Passport of J. Howard Wainwright, 1861

MyRye.com is pleased to be working with the Rye Historical Society on Papers from our Past. The Rye Historical Society Archives contains centuries of stories, from everyday life in Rye to significant events in American History.

by Alison Cupp Relyea, Director of Programming and Education for the Rye Historical Society

For the vast majority of Americans who hold passports, those cherished booklets are now sitting in a drawer somewhere, possibly expired, collecting dust for over a year as we wait for the risk of COVID and mandatory quarantines to begin to fade. More people are spending their days at home in Rye, and at the Rye Historical Society, this gives us an opportunity to dig through our town’s past, exploring drawers full of papers and photographs. In one of those drawers, we have a passport belonging to Mr. Howard Wainwright.

The Wainwright family history is intertwined with Rye’s history, primarily through the Wainwright House on Milton Point. It is a history that spans centuries, with notable family members celebrated for their contributions ranging from military service to human rights and commitment to the arts. John Howard Wainwright was born in 1829 and lived until 1871. He and his wife, Margaret Livingston Stuyvesant Wainwright, purchased Milton Point in 1864. She is a direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant. The family lived in New York City at the time and spent summers in Rye with their children. Their youngest son, Colonel J. Mayhew Wainwright, built the Wainwright House.

Looking at this single document, a passport for J. Howard Wainwright, we can pose some questions, the answers to which teach us about much more than the history of this man and his relationship with Rye. This document connects to the history of our country and gives messages about identity – who mattered in the eyes of our government and why.

Passports were not always a requirement for international travel. In the 1700s and 1800s, it was typical for people to travel across national borders between European countries and even overseas from the United States without any documents, which is partly why this passport is historically significant. Why did Mr. Wainwright have this passport issued on “the 5th of November, 1861, in the 86th year of the Independence of the United States”?

While passports were not required for transatlantic travel until the mid-1900s, wartime was different. This passport was issued at the beginning of the American Civil War, lining up with one of the only exceptions to this rule. As stated in the National Archives entry on passports, passports were:

Not Required. As a general rule, until 1941, U.S. citizens were not required to have a passport for travel abroad. Exceptions to general rule: Passports were required from August 19, 1861, to March 17, 1862, during the Civil War.

Wainwright’s passport, issued on November 5, 1861, fell within this short period. Nations at war had different security needs, and the US requirement during the Civil War was consistent with documentation required by European nations during wartime. Mr. Wainwright’s travel to England was likely a family trip, but as it fell in that window, it required documentation. While the passport requirement was lifted for international travel in 1862, the Union and the Confederacy had their own rules regarding documentation for passage across their borders for the duration of the war. While one would expect this passport to tell a story of international diplomacy, its existence reflects conflict on US soil.

Wainwright’s passport is also a primary document to better understand the history of women and gender norms in our country. Women did not carry passports at all at that time, and as is stated on Wainwright’s passport, they were included within their husband’s travel plans, with the language, “Mr. Wainwright is accompanied by his wife.” Even later, when women were permitted to carry their own passports, they were required to do so under their married name, as Mrs. Howard Wainwright, for example. This made it extremely challenging for single women to obtain a passport and travel. Women’s history and the definition of identity are forever entwined.

In the past year, we have seen borders around the world close in a way we never imagined, a different type of war pushing leaders to do their best to protect their countries. Over time and collective healing, what stories will our documents tell future generations?

For more information on the history of passports:

The New York Times Papers, Please!

CN Traveler How the U.S. Passport Evolved from Status Symbol to Essential Travel Document

The Guardian A brief history of the passport

National Archives Passport Applications

(Edited to reflect correct passport date of 1861)